The price of being a good neighbor can be steep for banks foreclosing on condominiums and homes in planned communities.

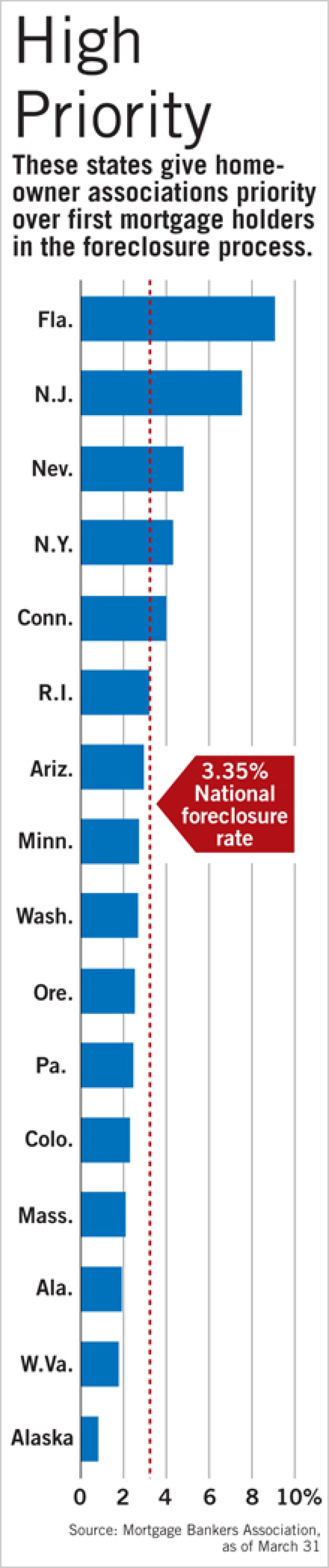

In 16 states and the District of Columbia, homeowners associations have "super lien" priority ahead of the first mortgage, meaning they get to collect unpaid dues and assessments before a bank can foreclose. (In the other 34 states, HOAs are wiped out by a foreclosure.)

Many financially-strapped homeowners associations are holding up loan modifications, short sales and the sale of foreclosed properties as they try to strong-arm servicers into paying amounts above and beyond delinquent dues. Some homeowners associations have even initiated foreclosure proceedings against banks. Others are demanding that thousands of dollars be set aside in escrow accounts to cover needed repairs before a foreclosed home can be sold.

"It's a hot topic because the fees can grow quickly," says Cameron Larkin, a vice president of finance at Nationstar Mortgage Holdings Inc., a top subservicer for Fannie Mae. The highest charge Larkin has seen was $39,509. He called the amounts "pretty amazing, where the dues are as high as $20,000, and it's layered with legal fees."

Jon Goodman, president of the Denver law firm Frascona, Joiner, Goodman and Greenstein P.C., says HOAs are so overwhelmed by foreclosures "they are desperate to get any nickel they can."

"The argument that HOAs should be senior to everything is like property taxes — they are part of preserving the collective value of the neighborhood," says Goodman, who represents servicers, HOAs and investors in distressed properties. "Lenders make loans in those states mindful that they have to deal with a six month super-lien, but not other junk expenses. The question is, are the associations going overboard? Maybe it's a case where they should get $500 but they're asking for $3,000."

The statutes governing HOAs vary state to state, but in states where super-lien priority exists, HOAs can generally collect up to six months of overdue fees and dues. In Florida, though, the lender has an obligation to pay 12 months of assessments and dues, or 1% of the unpaid principal balance of the loan, whichever is the lesser amount. In Nevada, an obligation to pay up to nine months of unpaid dues is standard, but the statute there has been interpreted to include late fees, collection fees and any violations for the nine months before the bank took control of the property.

The issue is compounded by the fact that there is no central database identifying whether a specific property address is a member of an HOA.

The associations have leverage over the servicers, says Cliff White, director of operations at Association Protection Services, a Denver law firm that represents banks and servicers. Servicers often find out about past HOA dues after filing a foreclosure notice or when they are selling a foreclosed home.

"They have to settle up with the HOA before they sell the property to a third-party and if they don't the HOA has recourse to foreclose," White says.

It can take four to six months for an association to find the right person to contact at a servicer shop, says Matt Martin, the CEO of Matt Martin Real Estate, an Arlington, Va., asset management firm. Even when HOAs send letters demanding payment, the lag time results in more fees. So-called "junk fees," including legal fees and late fees of $20 a day can easily add up to $10,000 to $20,000.

"Servicers have spent tens of millions on junk HOA fees," Martin says. "It's a huge problem."

Florida is the "lion's den" when it comes to problems with homeowners associations, says White, who has seen HOA fees in excees of $100,000. He estimated that 15% of properties with an HOA have some type of "escalated issue, whether it's the HOA actually foreclosing or charging junk fees or holding the bank liable for assessments before they were responsible for the property."

One of the most egregious costs servicers have been asked to cover is a $500 fee simply to get a copy of the past due account balance, White says.

For now it seems the responsibility rests on the shoulders of the servicers. Nationstar, for one, is trying to be proactive by identifying borrowers who have not paid their dues before a loan goes delinquent.

Other servicers are taking a more combative approach. PennyMac Loan Servicing LLC, for example, filed a lawsuit in February against the Palm Breeze Executive Townhomes Homeowners' Association Inc., in Homestead, Fla. PennyMac claimed the association interferred with the sale of a property by demanding $12,217.65, including unpaid back dues that had accrued before it took title. It wants to pay only what's allowed by state statutes.

"Lenders are becoming very savvy about what's outside the statutes," says Lisa Magill, a shareholder at Becker & Poliakoff, in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., who represents HOAs.

But servicers aren't exactly innocent victims either, Magill says.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac require that servicers foot the bill for any past HOA dues up until a property is sold.

"When we are made aware of delinquent HOA dues, we immediately engage with the servicer to address the situation," said Fannie Mae spokesman Andrew Wilson. "For HOA dues, fees and assessments from before the foreclosure, the amount Fannie Mae reimburses servicers depends on a number of factors, including whether the payments were necessary to protect the priority of our mortgage lien and the provisions of state laws."

When servicers rack up late fees, though, Fannie Mae won't pay.

"It's certainly an expense issue because there's only so much Fannie Mae will reimburse us for," says Larkin. "The industry marches to the tune of Fannie Mae and if they are not yet ahead of this issue, it means nobody is."

Yet servicers are loathe to pay for the expenses out of their own pockets. Often they wait to stick the new borrower purchasing the foreclosed property with the past dues or pay the dues from the sale proceeds.

Private-label investors have pooling and servicing agreements that restrict servicers from passing the dues on to them as well.

In May, Martin established Sperlonga Data and Analytics LLC as a free service for HOAs to enable them to input documents into a portal and have the information sent directly to the servicer. But with more than 300,00 association-governed communities in the U.S., encompassing 24.8 million American homes and 62 million residents, creating a thorough database will be a daunting task.